Webinar: Citizen Science in fragile contexts and with marginalised communities

One of the final HEIDI Project events was to organise one more webinar on a subject close to UCL ExCiteS‘s heart: reaching those underrepresented in science and citizen science. It is often hoped that citizen science will help democratise science, which in turn will help us do science better by finding hard-to-reach information. But this cannot happen, and it cannot benefit humanity so well, while there is unequal representation.

The webinar was held on 9th December 2022, and the speakers were Rafael Chiaravalloti of UCL Anthropology and Eugenia Covernton of Lecturers Without Borders, who also works on the HEIDI Project.

Rafael Chiaravalloti: The Pantanal Wetland

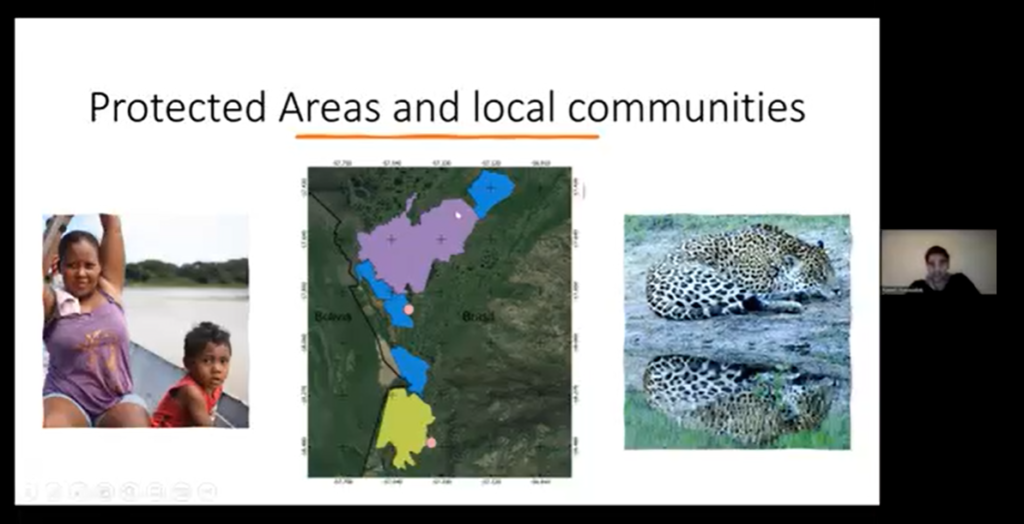

Rafael told us of his work with NGOs in the Pantanal Wetland, Brazil. This is a vast floodplain area of over 200,000 hectares, with a very high density of endangered species including the jaguar, the blue macaw and the giant otter. Perhaps because it is a wetland, there is a low rate of deforestation and it is one of the most strictly conserved environments in South America.

Some of the people and a jaguar in the Pantanal Wetlands, from Rafael’s talk

It is a protected area, which meant that no natural resources could legally be used – not even by the indigenous people who live there. “They told everybody to get out,” a local person told Rafael. “They burned the houses so people wouldn’t go back.” Another displaced person said, “They took everything, we had to leave in a little canoe. So myself, my brother and my aunt were in a tiny canoe and we sank. In the middle of the bay. We could not save the dogs, the chicken, nothing.” The official narrative was that this was to protect wildlife. But in practice, there was physical and economic displacement, and there was violence. There was also, Rafael said, a narrative that local people did not belong – and there was no empirical data to show the impact of all this on the displaced people, nor to show the impact of the local people on the local environment.

Rafael worked with UCL ExCiteS to create a version of Sapelli with local people in Pantanal to create a local citizen science program to collect evidence of the impact of traditional fishing. The implementation of the plans, he said, was – as is invariably the case – challenging and never as straightforward as one imagines!

First, there was a need to reduce the quantity of data people were asked to collect. Initially they had hoped to collect data of 16 different species, and local fishermen for example needed to go through their phone for several minutes every time they caught a fish, so it was vital to simplify the process. Then there was the user interface: there was a local crab that people caught, and the graphics available for icons on the Sapelli program offered a picture of a red smiling crab which was an amusing, familiar sight to a Westerner but meant little to the local people. A scientific figure of the crab in question did make sense to them, and was used instead. Then it was found that even “the most unbreakable phones in London” were very easy to break in the Amazon rainforest for one reason or another.

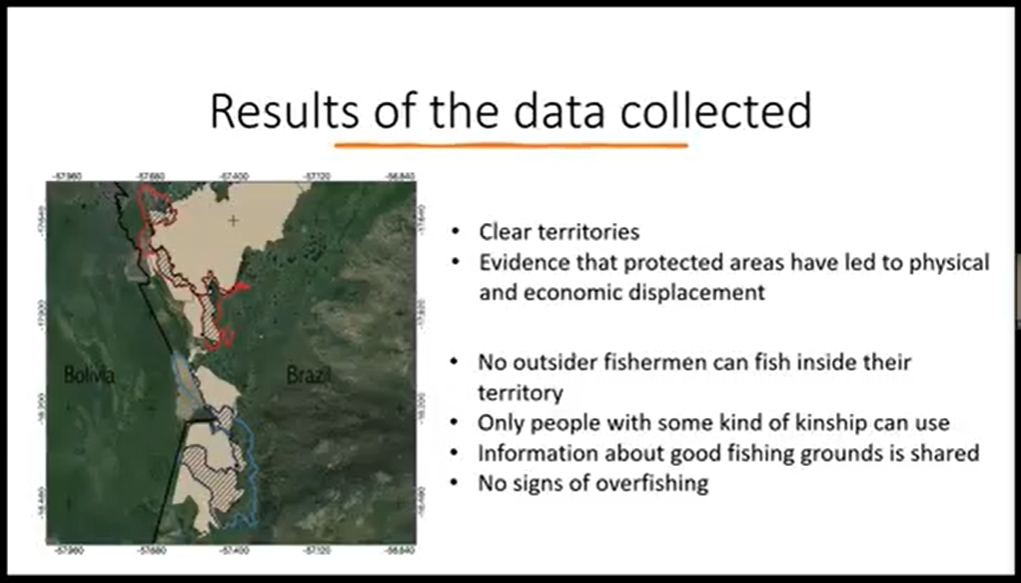

Nevertheless, Rafael and the local community employed a participatory approach to data collection, and Rafael added some other studies such as satellite data of the area and an ethnographic approach, including living in the area for an extended time. They developed a map, which showed that in fact the local people were fishing sustainably with traditional methods. There are many such case studies with similar results, which you can read a paper about here and a storymap here. Rafael told us that for such studies to work, three things must always be present: trust, community led decisions and adaptability of the data collection method. (One major difference in the data collection phase was the timing; it varies between regions and communities from 2 weeks to 15 months. Rafael also told us that in some communities, people prefer to use WhatsApp rather than Sapelli, as it is already familiar to them.)

Some of the project outcomes, from Rafael’s talk

The outcome of the project was that the community approached Brazilian policy makers with the evidence they had collected. It took 2-3 years, but after this, a new community reserve of 5000 hectares was created, from which local people may not be displaced. They have regained some, though certainly not all, of their traditional territory. Rafael is happy to answer questions by e-mail.

Eugenia Covernton: Lecturers Without Borders

Eugenia grew up in a small town in the centre of Argentina, 250km away from a university. She noticed that, increasingly, universities and academic institutions are actively working to increase their outreach activities, particularly those geared towards children and the wider population. However, most of these activities tend to take place near the institution. To rural populations, this means access remains limited except to those with the financial resources to travel.

She also noticed that scientists can feel inequality: for example, some institutions have higher outreach budgets than others, and some researchers may be doing brilliant work but no support to share it with the world. Underrepresented scientists thus have less visibility. Many young people may be unaware of brilliant scientists within their own communities.

Teachers around the world, Eugenia told us, are actively trying to engage students in STEM subjects. They want hands-on activities, project-based learning and pedagogical tools. But resources available to schools varies a great deal from one place to another around the world.

All of these situations, Eugenia felt, preserve inequality of access to STEM learning and careers. And so she, along with three friends, founded the NGO Lecturers Without Borders.

A lecture on Citizen Science taking place in Laos from Lecturers Without Borders, from Eugenia’s talk. Lectures are on a variety of STEM subjects, but some schools have started citizen science projects!

She emphasised that her talk is not limited to citizen science, because Lecturers Without Borders (shortened to LeWiBo) encompasses all STEM subjects. They aim to give children and young people access to STEM subjects – and, in time, STEM careers – in order to teach critical thinking from an early age and to empower them for the challenges of the 21st century.

LeWiBo began in 2017. It started small, a network of friends in STEM careers making personal connections: for example, if a researcher was going on a trip to a conference or a family visit, they would reach out to people they knew in that area to ask if any local school wanted to host a visit. This allowed science to come to small towns where science events are not usually hosted. The network began to grow.

Then, of course, along came 2020 and most trips and in-person events were quickly cancelled, including the closure of many schools. LeWiBo rapidly adapted, offering webinars instead of in-person lectures. In one sense, this allowed them to grow rapidly, reaching more schools and also reaching students in their own homes. Many schools began requesting events, and LeWiBo created some special projects. Talks were created specially aimed at children rather than at fellow scientists. Time zones were crossed – a scientist could give a talk at their 9pm which was heard by students on the other side of the world at their 9am.

One of Eugenia’s favourite results was that this gave voice to scientists from the Global South. A mathematician from Nigeria gave a talk in Austria, and the students were thrilled to discover that such research was done in Nigeria (LeWiBo always collects feedback on the talks from schools), allowing scientists to counteract stereotypes and distorted images about who can be a scientist and where science is done. (Students’ questions – and thus perceptions – vary from place to place; for example, questions about astronomy are often asked by students in light-polluted cities, and questions about genetics by students living in rural areas.)

However, there were problems to going online: many schools and homes across the world have no Internet access. Schools in Nepal, Laos, Pakistan and Indonesia, and also Peru and Bolivia, had become very engaged with in-person science, but had to pause their activities when in-person events were not possible. Some schools were continuing to teach using WhatsApp (similarly to what Rafael had found!), such as in Egypt, Senegal, Ghana and Kenya; webinars were not possible, but they could send information and resources and allow for questions and answers. All this lacked, of course, the novelty and personal connections built up through in-person lectures.

Some of Lecturers Without Borders’s past lectures and activities, from Eugenia’s talk.

Today LeWiBo is starting to reorganise both online and in-person events. They now have >320 scientists, >50 countries and >1000 schools involved. Besides the benefits of children meeting real scientists, new knowledge, cultural exchange and tools to fight stereotypes, scientists are also offered (non-compulsory) coaching for talking to young audiences, so can develop their communication skills. Eugenia aims to create a new version of the website in which resources can be made available, a Code of Conduct drawn up and communication can be facilitated in a safe way (scientists cannot all communicate directly with children for safety reasons, and because LeWiBo has a small voluntary staff, this has become a bottleneck). She also aims to do a particular focus on women in STEM, challenging children to go and find a woman scientist in their communities – this will help them find role models and promote women as role models in STEM.

A major challenge for all this is funding: LeWiBo is still run by a voluntary staff who must do other work to earn a living. Nevertheless, Eugenia’s dream is that all scientists become comfortable with visiting schools, and all schools become comfortable to host a scientist. Like Rafael, she is happy to be e-mailed with questions.

We can definitely see many common themes in Rafael and Eugenia’s fascinating stories of reaching indigenous or marginalised communities, and we thank them very much for their time to prepare them and come to tell us!

If you’d like to catch up on some of HEIDI’s past webinars, please check out our Citizen Science For All Talks YouTube channel. You will also be welcome to attend the HEIDI Project’s final event in May – you can register your interest here.